Self-Neglect is defined as a broad range of behaviour in which an individual is neglecting to care for their personal hygiene, health or surroundings. It can be a choice by the individual or it can be because they are unable to look after themselves. Either way it is often indicative of further safeguarding concerns.

As self-neglect is such a broad and complex safeguarding concern it can present itself in a wide variety of ways. Often signs of self-neglect only appear a long time into a period of neglect and some signs are more difficult to spot than others but professionals should be on the lookout for….

Poor personal hygiene Missed appointments Unsuitable Clothing

Unusual odours Forgetfulness

Unusual odours Forgetfulness

Messy presentation Dehydration

Hoarding Poor diet  Build-up of waste in the home Unexplained Weight loss Dangerous living conditions

Build-up of waste in the home Unexplained Weight loss Dangerous living conditions

Infestations  Non-functioning utilities Threatened eviction

Non-functioning utilities Threatened eviction

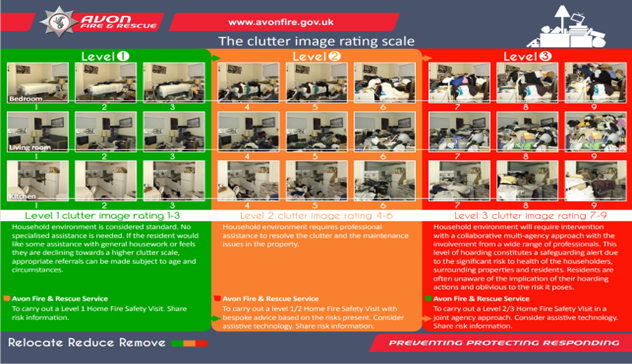

Hoarding is one of the most common forms of self-neglect and of course occurs to various degrees. This resource from Avon Fire and Rescue helps professionals to identify levels of hoarding and suggests appropriate courses of action:

For specific guidance on hoarding see our specific hoarding guidance.

If, as a professional, you come across an individual who you believe to be self-neglecting the first thing you should do is assess if they are at immediate risk of serious harm or are putting others at risk. If so, contact the emergency services as soon as possible.

If the individual is not causing an immediate risk and is not at an immediate risk themselves, then you should work to engage the individual in the process of them getting better. Find out what their wants and needs are and explain your concerns to them. Establish the wider picture, start to build a chronology and an idea of the individual’s network. Refer to the Needs Assessment form here (currently under review).

If an individual has care and support needs that mean they are unable to protect themselves from self-neglect and they are at risk of, or already experiencing, self-neglect then they may meet the criteria for a Section 42 enquiry under The Care Act 2014. In these circumstances, you should refer the individual into Adult Social Care. You can do this by clicking on the link here: Report suspected abuse (bristol.gov.uk).

If, for whatever reason they do not meet the Adult Social Care threshold, then a non-statutory Multi-Agency Risk Management meeting (MARM) can be called. Any professional can request a MARM if they have concerns about an individual who is at risk from self-neglect. Guidance on how to arrange a MARM in Bristol can be found here. You can also contact mental health services or the person’s GP if you see fit.

If an adult has mental health issues which effect their executive functioning (see guidance on executive functioning here: The person seems to say one thing and to do another - Capacity guide) or they have fluctuating capacity (as defined here: The person’s capacity seems to fluctuate - Capacity guide ) then a Mental Capacity Assessment will be needed. This can be undertaken by anyone with the appropriate training. You can book on to one of our Mental Capacity Act training days here: https://bristolsafeguarding.org/training/kbsp-training/ . Alternatively, contact mental health services and request a mental health capacity assessment to be undertaken by a professional.

It can be challenging to convince a person who is self-neglecting to engage with the plans and services offered to them but it essential that professionals keep in mind that the person’s neglect is most likely the result of complex trauma or serious health problems. Do not close a case solely on the grounds of non-engagement. As professionals, you have a wealth of tools which can help you break down barriers when an individual is struggling to engage. See pages 12-14 of our Self-Neglect guidance for more detailed input. If a person has mental capacity, is at serious risk of danger, and is refusing to engage, after exhausting all possible routes to engagement, a professional should approach the High Court to gain appropriate legal authority to intervene. Maintaining professional curiosity is paramount when working to engage individuals and it is important to remember that there could be a wealth of different situations which present as non-engagement. Recent learning from a Safeguarding Adults Review brought attention to a case where criminal exploitation was causing self-neglect.

If an individual is at risk of losing their home as a result of their self-neglect then you should complete a Homelessness Prevention Team referral here: Homelessness prevention referral from agencies (bristol.gov.uk).

The KBSP carried out a thematic review of self-neglect and have produced this flyer summarising the key learning: Self-Neglect Information For Practitioners

As stated above, often the causes of self-neglect are complex, unclear and multi-faceted. They commonly include:

Self-neglect can also be linked to Obsessive Compulsive Disorder or Diogenes Syndrome.

Adults who self-neglect are likely vulnerable to other forms of abuse as well as exploitation, domestic and sexual abuse, victimisation, bullying and radicalisation. Self-neglect can also be caused by any one of these.

The Care Act 2014 contains the legal definition of self-neglect and formally recognises it as a form of abuse. It places an emphasis on the importance of early intervention and prevention as well as stating that there is a duty for all agencies to work together to help individuals experiencing self-neglect.

A statutory enquiry will be triggered by Section 42 of The Care Act if an individual meets all three of the key requirements:

Although many individuals experiencing self-neglect do not meet the threshold for a Section 42 enquiry, the local authorities have the power to undertake a non-statutory safeguarding enquiry if they see fit.

The Mental Capacity Act 2005 should also be taken into consideration when helping a person with self-neglect. There is presumption of capacity but if there are concerns around an individual’s capacity then a Mental Capacity Act Complaint Capacity Assessment should be completed. This can be completed by anyone with the appropriate training. Our training on this can be found here: https://bristolsafeguarding.org/training/kbsp-training/ . In an urgent situation, an emergency application can be made to the Court of Protection.

Mental capacity is decision and time specific and so often peoples’ capacity fluctuates. If a person is deemed to have fluctuating capacity, professionals should wait until an individual has capacity where possible or, in emergency situations they can proceed with the person’s best interests in mind.

For more extensive guidance on self-neglect see our guidance here.